Grief has a thousand faces. Right now mine wears a pair of Groucho glasses.

On August 8th, my husband and partner of twenty years died of stomach cancer. Our eldest turned 13 three days before he died. Our youngest was 11.

Those are some of the facts.

Everything else, is experience.

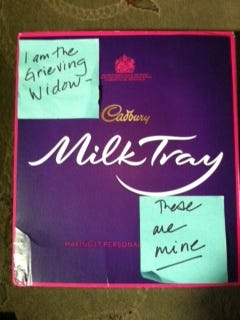

Trying to describe my experience, especially in response to the question, “How are you doing?”, is perplexing, mostly because of this mantle that was immediately draped across my shoulders, and which to date, has started to itch. Evidently I have become The Grieving Widow.

You all know The Grieving Widow: Crushed by sadness, she goes to bed for six months and can’t stop crying. She loses interest in her appearance, she doesn’t eat. Antidepressants are usually indicated. An alternate version of The Grieving Widow has her bravely keeping up appearances to preserve normalcy for her At-Risk Children. Anything she does outside the home — grocery shopping, showing up at back-to-school night, going to the movies — is “brave”. But she’s just going through the motions and it all goes by in a blur. She never enjoys herself, it’s all For The Children. She talks very quietly, Resigned To Her Loss, and sometimes grips a hankie dramatically just in case she starts crying again. She looks off into the distance a lot.

She Never Quite Gets Over It.

Clearly what I am actually experiencing does not meet The Grieving Widow standard. When I tell the truth, that we are doing well, I am often met with silence, or surprise, or a quizzical, squinting look that belies my listener believes I am Still In Shock, or In Massive Denial. I tend to launch into a lot of explaining of anticipatory grief, as if that should explain why we are doing well. It’s part of it, but not all.

We are sleeping ok and eating well and laughing. A lot. I am able to concentrate enough to read again. I’m able to shop for and cook dinner all on my own. We scattered his ashes in the Pacific last week and watched pelicans fly overhead and dolphins surf the waves we had just paddled through. Then we had a wonderful celebration on the beach. Then we went to Disneyland.

We go to the movies. To those amazing new trampoline places. We do art, sing out loud, kayak, make leis. We have been gratefully happy connecting with old friends.

It is a puzzling thing for me, these rules for my widowhood. I trained as a hospice volunteer 25 years ago and learned a lot about how we as a society don’t allow grievers to grieve. We get about three months after a loss, six if you’re lucky, to feel bad, and then there is significant pressure to snap out of it and get back to “normal”. I’ve seen that dynamic play out. But paradoxically, widows aren’t ever allowed to separate from their grief. So while I think we have made progress in understanding loss, and the emotional devastation that can follow, now that I am a widow, I am acutely aware that even while we are encouraging others to take more time and space with their pain, the linear, the flattened, gendered way we approach loss isn’t doing us any favors either.

Also unhelpful is the zeitgeist that compresses grief, or tries to, into a measurable, staged experience. Looking for what grievers have in common is a worthy endeavor. But it is possibly neglecting the wide variety of experiences out there. Mine is certainly no more definitive than anyone else’s, but most of what I find, read, or gets forwarded to me doesn’t fit at all. I find a lot of it condescending, maudlin, advice-driven, and dramatic. A very knowledgeable friend turned to me at the shiva and emphatically said, “You are going to be in pieces for a while. Give yourself a year”. To do what? Why a year? What if I don’t actually feel like I’m in pieces right now?

So much of what people think they understand about my family’s experience is projected onto us from their own lives. I’m learning a lot about others’ experiences, their own incomplete losses, their own imagination of loss. One of the condolence cards I received, from a colleague my husband worked with fifteen years ago, described his shock and sadness at hearing the news that he’d died, and he closed with his hope that I’d be able to go on. Wait, what? When I read that, I felt like a woman in labor with her first child, who hears another laboring woman screaming down the hall, and wonders, “My God how bad is this going to get?”

Let me be clear: my family went through fucking hell. Stomach cancer is a fucking ass wad jerk face motherfucking asshole motherfucker of a disease. My husband’s cancer grew into his esophagus, eventually making swallowing even a glass of water impossible. Over the course of his illness, he endured two rounds of the strongest chemotherapy (and radiation) that exist. Between each, he had most of his stomach and esophagus removed. In the end when he was actively dying, there were countless other procedures, and despite a feeding tube, he wasted away into something you see in pictures of Holocaust corpses. In the last weeks he had pneumonia and multiple infections and didn’t have the strength to cough or take a deep breath, or even to talk.

He also had no thorough exposure to palliative care. The way the system works is that the oncologists and surgeons are always first in line, so while they were constantly handing out intervention options and chemo protocols and suggesting clinical trials (that he was unqualified for), thinking they were offering hope, he was mentally buying himself more and more time in his own mind. In fact, he was declining rapidly and didn’t even have a DNR order in place. The palliative care doctors were amazing, but without the staff they needed, they could not significantly help my husband make truly informed choices on his wishes or figure out for himself what living well until the end really meant.

So I managed it. Or tried to.

And, how can I say this kindly as I possibly can, given the cruelty of what he had to face? My husband was not the best patient. If there even is such a thing. He initially had not been proactive about his symptoms, ignoring them until there was “lymph node involvement”, which is not great when you are dealing with a tricky cancer cell that is also aggressive. Gastric cancer research is seriously underfunded and doctors try to put the most positive spin on the statistics as they can, but his prognosis was probably dire from the beginning because he had waited so long to be diagnosed. He was understandably anxious and depressed, as the cancer progressed, he became increasingly disassociated, moving deeper and deeper into a fog. There was no spiritual epiphany or wake-up call that you sometimes hear about. He could not deal with what was happening to him, but there is a solid argument to be made that he simply didn’t have enough energy or time to add that to the list of things he had to reconcile. That’s what extremely aggressive cancers can rob us of, effectively. The ability to make meaning out of what is happening to us.

Consequently he did not want the optimal death experience I wanted to provide for him. He did not want to die. He resisted it until the very end. He was terrified to die, but he also loved me and our sons so very much and could not understand how or why he had to give all that up at 51 years old.

There were weeks when I would go to my office three or four evenings in a row, when I would be practically vibrating with rage and sadness and fear. I would cry so hard and so long my whole body shook and I gasped for air. I finally understood what it meant to be “wracked” with sobs. My body would ache all over the next morning. I have never felt so alone in my entire life. Stubbornly absent to my own suffering, I dedicated myself to the practice of compassion in the face of the difficulty created by and visited upon my husband, who could not fathom giving up every single comfort, hope, and dream he had to this disease. I also watched my children’s terror and confusion dance across their faces daily. Their suffering kept me up at night, fighting to accept that this was now part of their story.

Everything outside of his treatment was sidelined. We did not do very much in the way of fun. Fun things weren’t so fun anyway, when we did manage to rally. There’s nothing worse than the feeling that you should be having fun, and aren’t. Everything we did was measured against how much time or energy it would take away from my husband’s journey to wellness. Which wasn’t coming.

I worked harder than I had at anything I had ever done, to try and give him a good death and prepare my children for it, starting long before any of them could admit what was happening.

It was not an intellectual exercise. My heart was cracked open, over and over and over again, by my failures: to maintain my composure, to keep my feelings in check, to save my kids from their loss. I spent a long time feeling like a shitty wife and awful mother because I wasn’t Hospice June Cleaver. It took a long, long time to turn that Titanic around. Slowly, instead of railing against it all, I stopped trying to manage. It quietly occurred to me that maybe I was allowed to risk including myself in the experience of compassion I held for everyone else. I began to accept that my husband would never accept what was happening to him. Whatever the reasons were, I did not need to worry about them. He was as entitled to that death as any.

As he began the last stages of dying, I continued our family meetings as has been our way, but I didn’t include my husband anymore. I held my boys close and listened to them and cried with them. And I made sure they understood what was happening every step of the way.

When my husband became bedridden and unconscious, it may have looked from the outside like I was unable to think clearly, but I was continually practicing taking the very smallest of steps towards Life. Helping someone die and bearing witness to their dying, is demanding beyond anything I’ve ever done, including giving birth. I was way past any kind of recognizable exhaustion, but I always started my day my favorite way, by walking our dogs. I would get out into the sunrise and talk to the Universe and listen to what it said to my heart. I was often too tired to eat the delicious food that was streaming into our kitchen, but I forced myself. Our community, including family and dear friends that are like family, surrounded us and we were never left alone, not even at night when friends would take shifts sleeping on the floor by our bed. I let them, and asked for help, and said what I needed when they asked, and took in the love.

So when I say that we are doing well now, you should trust me. Not only are we strong again physically, but we are filled to the brim with the love of many, many good people. My children’s friends were absolutely remarkable in their support for them, consequently they carry no shame nor any need to hide the fact that their dad died this summer.

One way of looking at it is that my husband died a little bit at a time over two years. We marshaled every strength we had to cope, and it changed us for the better. I got to experience my own compassion, love, and kindness — for my family and the world, but also finally for myself, and most importantly, in response to how things actually were. I learned not to wait until people and situations were as I wanted them to be. Or as I thought they should be. Or could be. Or would be. Somewhere along the way I noticed that my sons had become more creative, kinder, funnier. Then finally I looked up from coping and realized I had too.

He died just as the dawn started to pink up the horizon. As he was passing, a level of ecstasy lifted the energy in the room so dramatically I woke up. I remember looking at his peaceful face and thinking, “Why am I feeling joy?” because I had not expected to rejoice for him. I felt elation grab me and it filled every cell of my body with utter joy. I held his hand and told him how happy I was for him, that he’d made it, that his suffering was over, crying tears of relief for him, so grateful that I had spent his last weeks gentler with myself and our kids, that we had taken the opportunity to forgive each other for what we didn’t know, and that we had begun to forgive ourselves a little bit too.

So when The Grieving Widow I am supposed to be comes alive in my consciousness, scolding that I shouldn’t be so silly, so profane, so alive, I turn to face her in my nose and glasses, proudly intolerant of worry. Poor thing, she just doesn’t know. I tell her we don’t have to keep suffering It won’t earn us the privilege to be happy. Screw THAT.

My husband’s death didn’t break me. It was a gift. It burned off anything that wasn’t essential to becoming the best, entirely whole version of myself. It taught me how to be gentle with myself, after being my own worst critic for as long as I can remember. I have a calm perspective that’s rooted in a vast quiet restfulness inside, that I access on a daily basis. It’s not something I grasp for anymore. There is lightness in our home, born of having come through intense, traumatic change with forgiveness and with the mark of grace visited upon our hearts.

When I finally accepted that what we were going through was impossibly, defyingly painful, and stopped trying to keep the waves from crashing into our lives, suffering stopped having power over us. Somehow, impossibly, I gave my consent to let our lives be what they were. Vulnerable. We were aided in this miracle, every step of the way, by the love of dear ones in our lives. The stunning kindnesses we received everyday became equal in stature to the loss. Maybe more so.

Death is the greatest surrender we will ever face, a returning of our selves back to Life itself, and it will happen soon enough. I refuse to do it one second before I have to. The work of my grief is to answer the invitation back to a life made new.

Joy is not earned, by anything, ever.